Who Is Ludwig?

Ludwig II of Bavaria (1845-86), "the last Bavarian king", also called "the fairy tale king", an eccentric ruler and major patron of the arts who died mysteriously the day after being deposed on grounds of mental illness.

By Way of Comparison

Ludwig is unlike any film I've seen. The things I felt while watching it were similar to feelings I had watching Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Jubilee, the more experimental of Herzog's '70s movies, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and some things by Peter Greenaway.

Tech Spex

German, 1972. Dir. Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. Color. 2 hours, 20 minutes; broken up into two parts of roughly equal length. 28 scenes, each introduced by an intertitle. Low-grade film stock, projected at the Anthology Film Archives theater from a DVD that was clearly mastered from videocassette. It was full-screen and didn't seem trimmed, but I can't be sure.

More Importantly

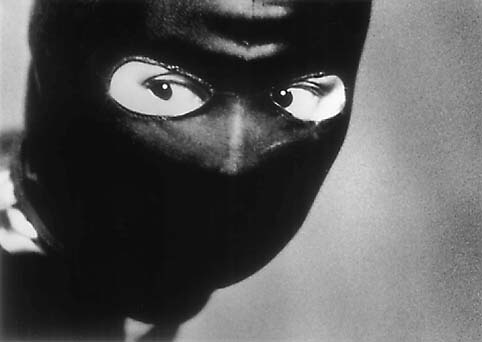

The movie consists mainly of Ludwig ranting over the music of Wagner. We become familiar with his favored court, a small group of men, and his favored topics, a small group of complaints. Sometimes the Wagner melts into pop music from the thirties, and there are moments when bits of American radio serials like "The Shadow" and "Superman" can be heard. Some actors play multiple characters, and some characters are played by multiple actors. Some scenes are more surreal than others, and at one point there is a dancing Hitler.

The shots are composed and lit like paintings. Nude human-statue babes hold torches or lounge in almost every scene. The entire thing was shot on a stage with lots of smoke, minimal props, and 19th Century art back-projected onto a sheet behind the action. This makes the depth of field odd, especially when Ludwig's shadow is cast onto the open world behind him. The art thus projected includes landscape painting, wallpaper, and architectural sketches/designs. Sometimes the result looks pretty crappy, but sometimes it's sublime.

Three unexplained color-tinted blurry handheld close-up interview-style monologues from minor characters are really wonderful.

What the Author Said

"The story of the last Bavarian King with his euphoria, his anxieties, his dreams told in a style of an oratorio or a medieval passion. Present and past are combined in a film of Wagnerian scenes, music of the thirties, Bavarian legends, ‘Oktoberfest’ waxworks, magic lantern, still life, surrealism, elements of silent films, guillotine, quotations from Goethe, Brecht, Valentin, and Shakespeare" --director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg

I missed most of that stuff but I still liked the movie.

A Challenge

While being able to appreciate a good shot here and there, I was bored by the mostly static shots, I was baffled by the poetry, I rolled my eyes at the theatrics. Then about halfway through something clicked and I figured out how to watch it. After a particularly melodramatic monologue, the king walks away from the camera, then stops and kneels. Snow pours down and a beam of light falls directly on him. The shot is among the most gorgeous I've seen in any movie, and it holds while the Wagner swirls and swells. I'd guess the shot is nearly five minutes long, totally still except for the falling snow. I was able then to follow the music as if what I were doing was listening to music, and to see the image as if I were looking at a painting, like I would in a gallery, listening to music and enjoying a painting at the same time. This was the key, to approach each scene as a combination of other art forms: drama, poetry, historical literature, painting, sculpture, orchestral music, and kitsch. I've never thought of a movie in those terms before, but with this in mind I was able to navigate through the world of Ludwig, and in this way my sensibilities, patience, and approach to cinema were all expanded.

Past is Still Past to the Past

I still missed a lot, though, because of my minuscule knowledge of German history, which is what the film is actually about. From what I've read, Syberberg's theme is always along the lines of "what made the Nazis?", and Ludwig writhes under the shadow of German history between his death and World War II. I excitedly await this film's return to me, when I shall be more ready to access it- though I'm not sure I could handle this type of material for seven hours, which is what his later Our Hitler, also playing at Anthology this month, seems likely to be.